On a recent Saturday morning, some 1,000 people crammed into Paper Tiger, a live music venue in The Strip, a trendy neighbourhood in San Antonio, Texas, full of bars, clubs and food trucks selling everything from mini tacos to lavender oat milk lattes.

But the crowd of mostly twenty and thirtysomethings was not there for a gig. Hundreds had queued for hours to attend a political rally in support of two young Democratic congressional candidates — 28-year-old Jessica Cisneros and 32-year-old Greg Casar — and to hear the headliner who has endorsed them: firebrand progressive congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

“We can send a message, because this is not just about Republicans and Democrats,” Ocasio-Cortez, 32, shouted amid cheers from the audience. “This is about electing representatives to Congress that actually give a damn about the people they represent.”

Texas will hold primary elections on March 1, making it the first state in the US to fire the starting gun on a frenzied midterm election cycle that will serve as a referendum on Joe Biden’s presidency so far, and determine which political party controls both chambers of Congress.

With the Democrats currently holding both the House of Representatives and the Senate by razor-thin margins, just a handful of races across the country could determine the balance of power in Washington for the next two years. The primaries, to be held in all 50 states this spring and summer, will set the stage for November’s general election, at which all 435 seats in the lower chamber and roughly a third of Senate seats are up for grabs.

For now, members of Biden’s party are laser focused on the Democratic primary in Texas’s 28th congressional district, where Cisneros, an immigration lawyer and political novice, is trying to do what Ocasio-Cortez did in New York just four years ago: unseat a longtime centrist Democrat incumbent in a leftwing primary challenge.

At the same time, Republicans are also eyeing up the seat, convinced they can build on the gains Donald Trump made in 2020 among working-class, socially conservative Hispanic voters, and flip a longstanding Democratic stronghold as they seek to ride the wave of Biden’s sinking approval numbers and take back the reins in Washington.

What happens in the far-flung majority Hispanic district, which spans a vast geographical area from the San Antonio suburbs to several hundred miles along the US-Mexico border, could signal where the Democratic party is headed ideologically, but might also prove decisive in determining who controls the halls of American political power for years to come.

A general election victory for Republicans would sound a death knell for Democrats’ grip on Hispanic voters not only in South Texas but in other conservative communities across the country. It would also upend, perhaps once and for all, the long-held expectation among Democrats that changing demographics would one day push Texas into their column at a national level.

“If [Republicans] picked up one [seat in South Texas], that would be surprising. If they picked up more than one, that would be seismic. It would signal that Republicans in those culturally conservative, traditional Hispanic communities, have found a language,” says Cal Jillson, a political-science professor at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. “That really cripples [Democrats’] whole demographic story.”

Ousting the King of Laredo

The incumbent congressman is no progressive. An anti-abortion, pro-gun Democrat, Henry Cuellar first joined the state legislature in the 1980s, and later served a brief stint as Texas’s secretary of state under then Republican governor Rick Perry.

Cuellar has enjoyed widespread popularity in the area he has represented since 2005, earning him the nickname “King of Laredo,” a reference to the large border city where he was born and raised. In 2020, Cuellar outperformed Biden in the district, winning 58 per cent of the vote to the president’s 52 per cent. Two years earlier, in 2018, the Republican party did not field a candidate, and Cuellar won with a whopping 85 per cent of the vote.

But progressives have sensed an opportunity to take another scalp and boost the numbers of the so-called “Squad” on Capitol Hill — particularly after Cisneros came within a hair of ousting Cuellar in the Democratic primary in 2020, when relatively low turnout and an energised left-leaning base helped her come within 3,000 votes of unseating the lawmaker she once interned for.

Two years later, with high-profile endorsements from Ocasio-Cortez, and senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, among others, progressives say the immigration lawyer and first-generation Mexican-American has a far greater chance of victory — especially after an unforeseen federal investigation shattered the foundations of Cuellar’s campaign.

FBI agents raided Cuellar’s Laredo home and campaign office last month. While the details of the investigation remain hazy, the probe reportedly relates to Cuellar’s ties to Azerbaijani businesses and politicians. The congressman has said he is “fully co-operating with law enforcement” and insisted the “ongoing investigation . . . will show that there was no wrongdoing on my part”.

Few public opinion polls have been conducted since the raids. But fundraising disclosures and interviews with more than a dozen local political operatives paint a picture of a Democratic ticket up for grabs, particularly as Cisneros has filled her diary with star-studded in-person events and Cuellar has largely retreated from the limelight.

Even before the FBI raid, polls showed the progressive challenger neck and neck with her rival. A Rasmussen survey of potential Democratic primary voters conducted in November put Cisneros on 36 per cent support, compared to 35 per cent for Cuellar, 7 per cent for “other” and 17 per cent undecided.

More recently, the Cisneros campaign revealed she had raked in over $700,000 since the start of the year — nearly five times Cuellar’s haul over the same period. Few colleagues from Capitol Hill have publicly thrown their weight behind Cuellar’s campaign.

But the congressman’s team sought to shore up support in the district last week by publishing a list of almost 200 local elected officials who had endorsed him. “Cuellar recognises he is in a dogfight, and he could potentially lose this thing,” says Jon Taylor, chair of the political-science department at the University of Texas at San Antonio.

Republicans spy an opportunity

Democrats are not the only ones keeping a close eye on the showdown between Cuellar and Cisneros. Republicans plotting to take back control of Congress see the Texas seat as one of their top targets nationwide.

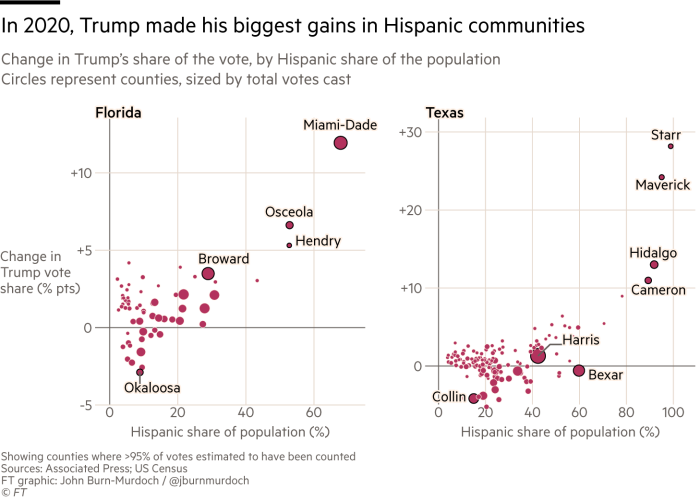

The party’s excitement is partly based on the fact that several largely Hispanic counties along the US-Mexico border posted huge swings towards Donald Trump and the Republican party in the 2020 presidential election.

Along with pockets of support in other states, notably Miami-Dade county in Florida, the results in Texas helped Trump improve on his performance with Hispanic voters nationwide by several points in 2020, compared to 2016.

Among the most remarkable swings was Zapata county, a largely rural, low-income area 200 miles and a cultural universe away from the food trucks of San Antonio. Hillary Clinton won the county on the Rio Grande river by 33 points in 2016, but Trump took back the area by a margin of just over five points in 2020.

Nearly 18 months later, Republican strategists say a combination of factors — from Biden’s sliding approval ratings to an influx of migrants crossing the border to rising consumer costs on everything from groceries to gasoline — will only accelerate the trend.

“This is Democrats’ worst nightmare in South Texas, because both [Cuellar and Cisneros] are very flawed candidates,” says one national Republican party operative. “No matter who we run against, the Democrat is going to lose.”

Non-partisan analysts are more circumspect, noting the latest round of redistricting — a once-every-decade process in which state legislators redraw congressional boundaries — has slightly favoured Democrats.

But nearly all acknowledge Biden’s party is in danger of losing its edge in the Rio Grande Valley, a strip of land that was once one of the few “blue” Democratic strongholds on Texas’s predominately “red” Republican electoral map.

“In the long term, the Democrats are on borrowed time in that region,” says J Miles Coleman of the University of Virginia Center for Politics, which downgraded its rating of the 28th congressional district from “likely Democratic” to “leans Democratic” shortly after the FBI raid.

“You have a bloc of voters that is working class, heavily Catholic, socially conservative, not being too jazzed by a more liberal Democratic party,” Coleman explains. “I really would not be surprised if those . . . seats in South Texas . . . are Republican by the end of the decade.”

Local Republican activists often describe the Trump era as a “coming out” for conservatives who had been afraid to articulate their concerns about an increasingly progressive Democratic party and felt emboldened by the former president’s bravado.

“It was not until the last four years that people really started to come out of the closet, to start voicing that the values we are being forced to believe in are not the values that we have in South Texas,” says Luis de la Garza, chair of the Republican party in Webb county, which includes Laredo.

De la Garza, a 66-year-old real estate broker, pointed to “family values” and “religious values” — a plurality of the district’s voters are Roman Catholic and favour tighter abortion restrictions — as well as a veneration for law enforcement, including the US Border Patrol which is one of the largest employers in the area, to explain the surge in support for the Republicans.

“The Democratic party has definitely left us,” de la Garza says. “President Trump was enormous in helping people come out and say it is OK to be a Republican.”

Jennifer Thatcher, the Republican Party chair in neighbouring Zapata county, agrees, saying of Trump: “He is the president that gave us a voice again.”

Thatcher, a 45-year-old mother of two who works for a home healthcare agency, cited her religious convictions and concerns about immigration to explain why she had switched her support to the Republicans in recent years.

“We are working class folk and we know what the value of the dollar is . . . we live at the border . . . we know what goes on,” Thatcher says, adding: “We believe in the family, the majority of us are pro-life. There is no pro-choice here.”

While Trump came under sharp political scrutiny for his family separation policy and other aggressive tactics at the US-Mexico border, official figures from US Customs and Border Protection shows a spike in land border crossings in the American South-West since Biden took office last year, with “enforcement encounters” reaching a high water mark of nearly 214,000 in July 2021 alone. By comparison, just under 82,000 encounters were recorded in July 2019.

Ross Barrera, the former Republican party chair in Starr county, says he and his neighbours did not “hate” migrants, but were concerned about an overspill of drug cartel-related violence in their communities. “Maybe we don’t need a wall, but we do need some type of saying . . . if you have crossed the border, you have committed a crime,” Barrera says.

A cautionary tale for Democrats

Republicans are holding their own primaries in the district to determine who will run against the Democrat victor in November. A record seven candidates have put their names forward in an area where just four years ago the party could not recruit a single candidate to run. Early voting patterns already suggest more people in the area are casting ballots in the Republican primary than ever before.

Cassy Garcia, a 37-year-old former aide to US senator Ted Cruz, is among the Republicans running, having already picked up the endorsements of the National Border Patrol Council — a labour union that has historically backed Cuellar — as well as the Susan B Anthony List, an anti-abortion group.

Garcia maintains she stands the best chance of beating Cisneros, whose platform includes a commitment to Medicare for All, more liberal immigration laws and an embrace of the Green New Deal, a progressive package of environmental policies opposed by many in the area who work in the oil and gas industry.

“If I go head-to-head with Jessica, that is going to be a very easy win for us, because we are a conservative community,” Garcia says. “We are not open borders, we are not socialists.”

Cuellar’s advisers are keen to emphasise the incumbent’s conservative credentials — and make the case he stands a better chance of staving off the Republicans than his progressive challenger in the atypical Democratic district.

“The congressman is a really great fit for the district at the end of the day,” says one Cuellar campaign official. “You have a lot of Republicans voting for him in a general election, on top of moderate Democrats who may not be very happy with the national Democratic message.

“I don’t think that is the case for any of the other primary candidates,” the aide added, in a thinly veiled reference to Cisneros. The Cisneros campaign declined to comment for this article.

Most Texas politics-watchers say despite Cisneros’s well-resourced primary challenge, and the dark cloud of the FBI investigation, they expect Cuellar to eke out victories in both the March primaries and in November.

Chuck Rocha, a Democratic political consultant and founder of Nuestro PAC, a group that works to turn out Latino voters, said he would “not want [Republicans’] odds in a poker game” in the Rio Grande Valley.

But he added the party’s inroads in the area should serve as a cautionary tale for the Democrats as they look to shore up support among Hispanics heading into November.

As Biden and the Democrats’ approval ratings have fallen nationwide in recent months, some surveys suggest their standing has fallen more sharply among Hispanics than other ethnic and minority groups.

“Demographics is an opportunity, not a destiny . . . the work still has to be done to tell young voters in Texas why they are Democrats,” says Rocha. “We just always assumed wrongly because their mommas and daddies were Democrats that they would be Democrats, and that is a false narrative that Democrats are learning the hard way.”