Rodney Marsh was a popular and talismanic figure in Australian cricket for over 50 years – as a player, commentator, coach, selector and administrator. With his walrus moustache, bandaged street fighter hands and grizzled wit, he came to personify an era of hairy, thirsty, newly professional modern players.

As Test wicketkeeper from 1971 to 1984, Marsh was Australia’s field marshal, setting the tone for energy and effort, and upping the ante when required, be it with a dry-yet-devastating word in a batsman’s ear or an encrypted gesture to a fast bowler at the top of his run-up. Although it hurt him deeply to never captain his country, that tactical nous and feel for the game and its players later made him a notable success as an academy coach around the world.

Marsh’s great-grandfather, Dan, had been sent to Australia in 1868 on a manslaughter charge after a late-night scuffle in Derby, UK, resulted in a man being shot. Despite a coroner finding no intent, Dan Marsh (after whom Rod named his son, later a Tasmanian captain) served five years in Fremantle Prison before establishing himself as a pillar of the Geraldton community.

Like his ancestor, Rodney Marsh’s destiny was always in his hands. “Mum wanted me to be a pianist,” he would reflect. “But I wanted to be in the game.”

Marsh first put on wicketkeeping gear for Armadale Under-16s, aged eight. Even then tough as old boots (he didn’t own shoes until he was 10), he had honed his game in fierce backyard “Tests” against brother Graham (a future golf star) with father Ken urging them on. Both boys were state cricketers but Rod rose faster, captaining Western Australia schoolboys at 13 and scoring 104 on state debut in 1968-69 against a West Indies attack of Hall, Griffiths and Sobers.

Despite an appetite for the local crayfish and Swan Lager, Marsh was made Test keeper in 1970-71. It was a controversial decision. Marsh was a batter first, keeper second. But a shrewd panel helmed by Sir Donald Bradman knew the days of sleight-of-hand and stumpings were waning. The 1970s were to be an era of pace. So began the career of Marsh, the original batter-keeper allrounder and blueprint for Gilchrist, Dhoni, Boucher and Sangakkara.

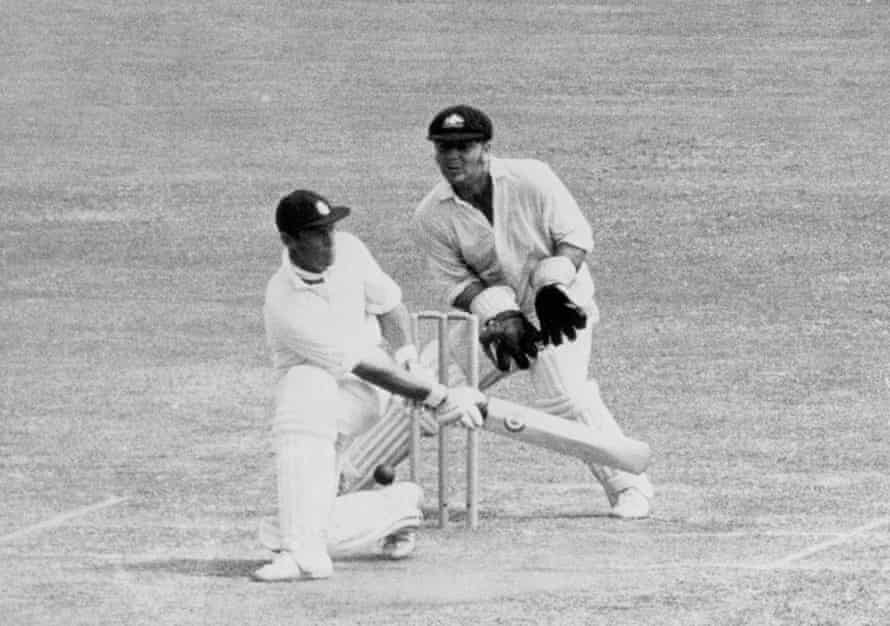

After some early fumbles, critics dubbed Marsh “Iron Gloves”. But he showed his steel by blasting 92 not out in his fourth Test, a then-record score for an Australian keeper. Moreover, by not grumbling about captain Bill Lawry’s declaration so close to a century, Marsh established his “team-first” trademark, a code that earned him undying loyalty from teammates and love from fans.

In the final Test of that first series, Marsh had caught John Hampshire off the bowling of another young debutante, one Dennis Lillee. It was the first of 95 dismissals “caught Marsh, bowled Lillee” in the 13 years to come. The pair had been mates since 1966 when Marsh was a trainee teacher with the University club and Lillee was a tearaway with rivals Perth. “I know from the way he runs up; the angle and speed, where he hits the crease, where the ball will go.”

English fans got their first look at Marsh when he pouched five catches and pillaged 91 runs, 60 of them in boundaries in 1972. He ended the series with 23 victims, a new record for Ashes Tests. Back home he carted his highest score, 236 for Western Australia, then hit 118 for Australia against Pakistan making Marsh the first Australian keeper to make a Test ton. He was to notch two more, 132 against New Zealand in 1973-74 and a match-winning 110 in the 1977 Centenary Test at the MCG, an innings he later rated his greatest.

Ever staunch, Marsh joined his mates in joining World Series Cricket in 1978. It doubled his income (still one-tenth what Graham earned on the PGA tour) and his marketability, as Marsh put his name to books and endorsements (the strangest bore the tag: “What does Rod Marsh do with his Vaseline?”)

But it came at a cost for wife Roslyn and their sons. “The early days of WSC, it was really hard on the family… there were some nasty telephone calls.” It also, Marsh believed, cost him the captaincy. That hurt him – and the team. Kim Hughes never won over the old war dogs Lillee and Marsh and their dissent was evident in the 500-1 wager they took under his captaincy in 1981, a sour dividend when Ian Botham won England the unwinnable at Headingley.

Like many of the era, Marsh was partial to a “malt sandwich” or three… or 43 (the flight to England in 1977) or 45 (en route to the 1983 World Cup). Such excesses may have impacted his batting – he averaged 33 in the first half of his career, 19 in the second – but his keeping got better in leaps and bounds.

Marsh’s goalkeeper dives and sky scraping catches, raucous appeals and grinning celebrations made for pyrotechnic TV. He was still able to cut short balls, drive half volleys and splinter bats too. In an 1980-81 ODI, he famously plundered three sixes, two fours and 26 runs from Lance Cairns’ final over.

Marsh was also a gatekeeper to baggy green culture and a key-master of its conscience. It was he who first co-opted Henry Lawson’s 1887 poem, Flag of the Southern Cross, into the Australian team’s victory song, albeit with a very Marsh modification (“Australia, you little beauty” became “you fuckin bewdy!”) And it was Marsh crossing his arms and shaking his head at captain Greg Chappell, mouthing “Don’t do it” when the underarm ball rolled down in 1981.

To the end he was defiant. “I’ll give those young blokes something to chase,” Marsh said in 1984, his final season. He did – 355 Test dismissals. And as founding director of both the Australian (1990-2001) and England academies (2001-05), he also gave young players something – and someone – to revere.